What I’ve learned about UX design from an AI music project

How much can creative side-lines teach us about design?

I have a confession to make: for the past few months, I’ve been leading a double life.

By day, I’m Andy — a lead content designer working in local government who’s also studying for a degree in Digital UX.

But by night, I’m Eternity Arcade — an experimental YouTube project creating retro, synthwave-influenced music and artwork made using AI.

Since March, I’ve spent a lot of time using Suno, which has emerged as one of the leading AI music platforms (along with Google’s effort Udio). You can use these tools as a complete musical sandbox, but I’ve used Suno almost exclusively for Eternity Arcade.

Initially, I thought this project would be a purely creative side quest. A fun diversion. I never imagined it would be relevant to my day job.

But the longer time went on, the more I realise I’ve learned (or re-learned) about design along the way.

Here are some of my takeaways…

1. Constraints and trade-offs

In his classic book Don’t Make Me Think, usability legend Steve Krug argues:

Design is all about constraints (things you have to do, and can’t do) and trade-offs (things you’re willing to sacrifice to live within the constraints).

This has really hit home to me working on the Eternity Arcade project. There are numerous constraints I have to live within. For example, the limitations of Suno:

- Music doesn’t always sound professionally mixed

- Vocals can sound unclear or heavily auto-tuned

- There’s only so much control you have over the output — no matter how good you are at prompting and other techniques

I’m also limited by my own skills: I’m not a singer or musician, and I find using a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) overwhelming.

But I need to work within all these constraints to achieve my goal: creating songs that I like enough to put out into the world.

And so I need to accept the trade-offs inherent in this experimental project. I have to realise when I’ve reached the point of diminishing returns working on songs. I must forget perfection and embrace ‘that’s as good as it’s likely to get’.

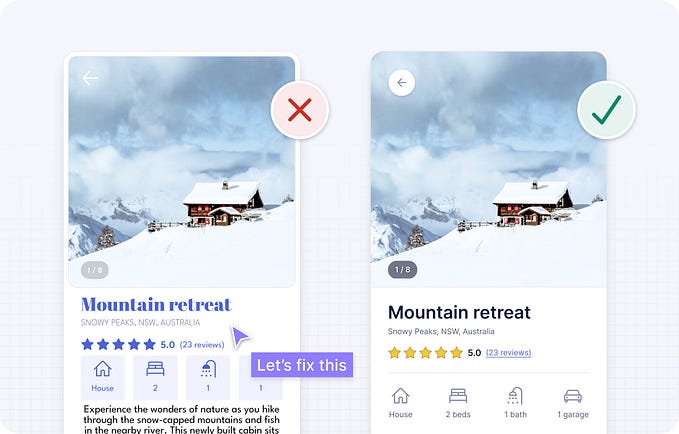

The same principle applies to artwork for video thumbnails (see below), as well as the videos themselves.

Even though I know this ‘good enough’ concept also applies when it comes to UX design, sometimes it takes a foray into a side-line to really refresh it in your mind — to effectively re-learn it.

The takeaway

Your design will never be perfect. This can be frustrating. But you have to accept when you’ve achieved ‘good enough’ results and move on.

2. Creative outlets

I’ve often found myself frustrated during a design project, but not quite being able to put my finger on why. It took me a lot of time and honesty to realise: I instinctively wanted to stamp my personal creative vision on every design.

Even though I’m fully on-board with collaboration, user-centred design and solution-as-a-team-sport in theory… deep down there was a part of me that wanted the design to be, well, my design.

But this mindset is professionally unhealthy, and obviously not what’s best for the project.

The project doesn’t belong to you. The product — even if you’re the ‘owner’ — doesn’t belong to you. The final work will be full of compromises, and will never, ever, truly be ‘yours’.

I’ve always had creative personal projects. But the past few months have hammered home to me just how important creative outlets are. They’re cathartic. And I think they make you a better professional.

If you have creative side-lines that give you full control, you don’t feel like you need to control everything in your day job. Your work doesn’t need to define you. You’re more willing to adapt, make compromises and act like a contributor, not a dictator.

The takeaway

Creativity and problem-solving are required in UX design, but there’s a danger in treating work as your creative outlet. Seek out side-lines for creative fulfilment, and stick to solving the problem as part of a team in work.

3. Side projects = new skills

It’s easy to get stuck in a rut in any design-related work. Same tools. Same processes. Day in. Day out.

Breaking the cycle isn’t always easy. But one way to do it is through creative projects outside work, especially if they require stepping outside your comfort zone.

Throughout my Eternity Arcade project, I’ve had to learn new skills and use new tools. Obviously I’ve had to learn how to get the best out of AI tools to generate music and artwork (mainly using DALL-E). But I’ve also improved my skills at image editing (for video thumbnails) and, more significantly, video editing.

You can see my progress on YouTube, as Eternity Arcade has evolved from publishing static-background videos to full-on music videos made from stock/archive footage — see one of the latest videos below.

In fact, Eternity Arcade is now as much a video project as an AI music project. And when AI video becomes readily available that’s going to be another game-changer.

My point in this section is that creative side-line experience can translate and benefit you as a design professional. My image and video editing skills are now far stronger than they were before. I’m confident using new digital tools, and I can bring that to the table in the workplace.

The takeaway

Doing new things forces you to learn new skills to solve new problems. This is great training for processes like design thinking which is all about finding different ways to solve problems.

4. Impact versus output

I read a great comment on a UX subreddit the other day that went something like this:

Design is about two things: identifying the problem, then designing a solution; many companies skip the first or second step, and sometimes both.

The point was that in the real world, far from design theory, business is about getting stuff done. Completing things. Churning it out. Making the stakeholders happy. You do things because the people paying the money want certain things.

It doesn’t always go this way, but it can do. A lot. Real work can be heavily focused output and not impact. In government, completing action plans and projects are too often considered successes in themselves— not the actual effect they have in the real world.

Working on the Eternity Arcade project has been refreshing. Instead of focusing on the amount of songs and videos I’m publishing (output), I can take my time, craft content and concentrate on engagement metrics such as views, likes and comments (impact).

This focus on impact over deliverables is very much aligned with the principles of Lean UX, which differs from more conventional user-centred design (see below).

Of course, we don’t always have the luxury of focusing on impact over output; it’s harder, and sometimes you just need to get stuff done. But this project has refreshed my thinking on the effects of your work.

The takeaway

Wherever possible, focus on the impact of what you’re designing — not the output/deliverables (completed projects, released products, shipped features). In general, advocate for the impact of your work, and not judging something a success merely by getting it done.

5. Reflection = improvement

In the same way it’s easy to fall into the trap of output over impact, it’s also common to race straight into the next project after completing the previous one.

Even in organisations that ‘value learning from experience’, sessions to reflect on how a project went can be rare. Why? For one, ‘lessons learned’ meetings can be seen as a waste of precious (billable) time.

But another factor is it’s uncomfortable to reflect on things that didn’t go well. No one likes admitting mistakes. And there’s a danger these things turn into a blame-fest.

But reflection is a powerful technique. Even if you don’t get to reflect as a group, individual reflection can be just as effective.

I’ve known for a while that reflective practice is important for continual professional development (CPD). But the Eternity Arcade project has given me a perfect illustration of just how useful it is, and how it can lead to improvement.

My first album of songs — The Infinite City (see below) — was created in a flurry of inspiration while using a new technology; I was creating songs as quickly as I could write lyrics.

This creative process was incredibly rewarding, I do really like these songs, and I was taken aback by how many positive comments they’ve gotten on YouTube.

But once that collection of songs was done, views and new subscribers began to dip and I was left with a natural window to reflect on what to do next.

How to improve on what I’d done before? Reflective practice, of course.

While there are many frameworks for personal reflection, the simplest is Jasper’s ERA model (see below). It’s very similar to the feedback loop of agile UX (test-learn-improve): you experience something, reflect on what you learned, then put those learnings into action to do better next time.

With Eternity Arcade, I reflected that while I loved the songs on The Infinite City, they weren’t well structured. There are, and probably always will be, limitations (constraints) on structuring songs using AI, but you can get better at crafting the output you want.

As a result of this reflection, what I put into action was a different approach for my next collection of songs — an album called Heat of the Night. These songs are far more structured, with proper intros, outros, clearer distinction between verses, bridges and choruses, as well as better instrumental solos.

This was all possible partially due to updated Suno models (the latest is version 3.5). But it was also a result of my reflections and commitment to learn new techniques with lyrics, tags, prompts and editing clips together into songs.

The takeaway

Reflection is important. It’s all too easy to jump straight into the next design project, and not learn anything from what you’ve just experienced. Make the time as a team or even just individually to reflect on lessons learned — and how to improve next time.

6. Embrace and adapt to AI

There’s been a lot of hand-wringing over the impact of generative AI on design-related jobs. Will AI replace designers? Will AI devalue design work? Will AI render the design industry obsolete?

The truth is we don’t know. We can be sure AI is a game-changer, and it’s having an impact. We can be confident that AI will continue to disrupt things — history teaches us this has always happened with new technologies.

The question is: what do you do about it?

My adventures in AI music have given me a fresh perspective on this, as music is another industry where everyone’s wondering how AI will change things.

For example, the emergence of tools like Suno and Udio has made some question whether the model of creators and consumers has changed forever. I can speak to this, as I listen to and enjoy Eternity Arcade songs like a fan (consumer), but I’m also responsible for them existing (creator). Using AI music tools doesn’t make me a musician, of course. But I have created something. And if other people like it too, then what I’ve created has value.

I think the best response to the uncertainty with AI is to accept you don’t know what’s going to happen, and throw yourself into getting the most of out new technologies.

That means learning and experimenting with AI. Be curious. Make mistakes. Find out how you can use it to achieve your creative or professional goals.

I think accepting, adapting to and embracing new technology is important — not just professionally but in life in general. It’s easy to laugh at older people who don’t ‘get’ the internet or social media (either on a technical or etiquette level). But that’s easy when you’ve grown up with that technology. For younger generations, AI will just be a fact of the world; something with positives and negatives, but an everyday part of life.

Failing to adapt to these seismic shifts in technology can age you and make you out of touch, fast. Resisting and rejecting AI will put me as a Millennial on the side of a line I don’t want to be on. And so I throw myself into projects like Eternity Arcade, to learn, to create, and be part of the future instead of left behind.

The takeaway

Accept uncertainty. Embrace rapid change. Adapt to a world in which AI is changing design, and everything else. Find a way to integrate AI into both your creative side-lines and professional work — or use it as a brand new opportunity that didn’t exist before.

About the author

Andrew Tipp is a lead content designer and digital UX professional. He works in local government for Suffolk County Council, where he manages a content design team. You can follow him on Medium and connect on LinkedIn.