Why are we Social: The Influence of being Social in Product Design

How social neuroscience could help in increasing user engagement and reducing the churn of products.

What do humans fear more than death? Oh, you know what? The fear of public speaking is even greater than the fear of death itself. Our fear of standing in front of a group of people is, at least in surveys, so high that we fear it more than death. Many would feel it as frightening to speak in public, and others would do almost anything to avoid it. Compared to the fear of death, the fear of public speaking seems minor. But the very idea of speaking in front of an audience can make most people anxious. How can the fear of public speaking be compared to the fear of death?

Why are we Social?

The answer seems to lie in our distant history, in our evolution as social animals. Social psychology research indicates that the evolutionary value of social inclusion for survival and the increased likelihood of rejection when speaking in groups is one of the reasons why public speaking is so terrifying. Part of the fear of public speaking comes from the fear that the public will ignore or reject them. From birth, because they cannot live alone, mammals rely on their caregivers for care and support. Later in life, by sharing resources and defending against predators, interaction with a social group increases their chances of survival. Thus, isolation from caregivers or social groups significantly reduced the chances of survival during evolution. Therefore, while social isolation is no longer a dangerous proposition, modern-day public speaking fear can be a trace of the evolutionary experience of man, where exclusion from a social group sometimes leads to death.

We often strive to avoid social isolation or social rejection and pursue social approval, a great motivator. We are determined to seek rewards that make us feel welcome, important, attractive, and included. In the digital world, we receive rewards in the form of instant dopamine gratification, such as hearts, likes, which are socially appropriate.

We are truly social beings. Our society is built on the layers of social interactions such as our families, acquaintances, colleagues, and business partners. As per one of the company research, nearly 70% of millennials say social networking apps are among their most commonly used.

Are we social only with humans?

Take a moment to understand the distinction between a rabbit, a train, a monster, a plane, and children’s toys. Although they are all different, in popular animated films they can all become main characters, and we can effortlessly assign intentions to them. The audience’s brain needs very few signs to take on the assumption that these characters are like us, so we can laugh or cry about their behavior. A short film made in 1944 by psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel showed the propensity to assign intentions to non-human characters. Two basic shapes merge and revolve around each other: a triangle and a circle.

People irresistibly impose stories on moving shapes. People who saw the video described it as a love story, a struggle, a chase, a victory. Heider and Simmel used this animation to explain how we easily interpret the social intentions surrounding us. Moving forms strike our eyes, but we see their meaning, motives, and emotion in form of stories. Since ancient times, people have witnessed the flight of birds, the movement of stars, and the swaying of trees, and have invented myths about them, describing them as propositional.

Not only is this way of telling stories a mania, but it is also an important clue to brain circuitry. It shows how prepared our brain is for interaction in society. Our lives, after all, are based on the ability to judge who our friend is and who our enemy is. By assessing the motivations of others, we manage the social world. Is she trying to be supportive? Is there a need for me to think about him? Are they out there looking after my best interests?

Our minds are constantly making social judgments. But does life experience give us this strength, or were we born with it? Studies have shown that even infants can judge the intentions of others. The brain is designed to judge who’s reliable and who is not.

We can’t help but connect with others, engage with them, care for them because we are social creatures by nature. This tells us why we assign personalities and emotions to not only digital interfaces such as chatbots, user-interface personalities, and also even to smart speakers. In the example below, try clicking on the “Unsubscribe” button. Even though we know they are all pixels, when we want to accomplish the task, to unsubscribe, we can still feel emotion or compassion.

Overlapping physical and social pain

Why do films make us scream, laugh, and breathe deeply? What do we have in common with our empathy for others, social rejection, and our physical pain? Rejection is also characterized by physical pain: “My heart is broken”, “I feel broken”, “It hurts”, “It was like a slap”. Instead of metaphors, these phrases seem to capture something that we cannot articulate directly about the essence of our feelings. Similar examples can be found not only in English but also in languages around the world. Is there a deeper connection between emotional pain and physical pain? Let’s know what happens in your brain when you are in pain.

Imagine that someone with a syringe needle stabbed your hand. There isn’t a single place in the brain where that pain is processed. On the contrary, several different regions of the brain, all functioning in concert, are triggered by the case. This network is summarized as the pain matrix. The surprising part is that the pain matrix is the key to our interaction with others. If you see someone being stabbed, it activates most of the pain matrix. Not the places that inform you that you have been directly affected, but those that have been linked to emotional interactions. Watching someone else in pain and being in pain, triggers similar regions of the brain. This is the essence of empathy. The pain matrix is the name of a group of areas that are involved when you feel pain. When you see someone in pain, many of these areas are involved.

Sympathizing with another person means feeling their pain literally. You make a simulation of what it would look like to be in their shoes. What makes stories like movies and novels so appealing and so universal in human society is our desire to do so. You will feel their agony and joy whether they are a stranger or a fictional character. You will become them, you will live their lives and you will find yourself in their place. You can try to convince yourself that it’s their problem when you see another person suffering, not yours — but the neurons in the back of your brain can’t tell the difference.

CyberBall Experiment

However, in a slightly softer context, an experiment by neuroscientist Naomi Eisenberger may shed some light on what happens to the brain (when we are excluded from a group). Imagine that you throw a ball to a few people and you are excluded from the game in a certain way: two other people throw a ball between them, leaving you out. Eisenberg’s experiment is based on this basic scenario. She asked volunteers to play a basic video game with two other players in which their animated characters threw a ball. The volunteers were led to believe that two other entities were just the other human players, but in reality, they were simply part of a computer program. The others played well at first, but after a while, they cut the volunteer out of the game, and simply threw between each other.

Eisenberg had the volunteers play the same game lying down under a brain scanner. She observed a remarkable phenomenon: the areas associated with their pain matrix were activated when the volunteers were removed from the game. It may seem insignificant not to get the ball, but to the brain, social rejection is so meaningful that it can actually hurt.

Physical pain involves many areas of the brain, some of which are responsible for detecting the location of pain, while others deal with subjective perception and discomfort of pain, such as the anterior insula (AI) and the anterior dorsal cingulate cortex (ACDC). In fMRI scans, Eisenberg’s team found that in participants who had been removed from the game, the AI and anterior dorsal cingulate cortex (ACDC) turned on. In other words, social pain stimulated the same regions of the brain as physical pain.

Why does rejection hurt? It may be an indication of the evolutionary significance of social bonds — in other words, pain is a mechanism that allows us to communicate and be accepted by others. We have integrated neural mechanisms that drive us to connect with others. This forces us to build communities.

Usage in Product Design

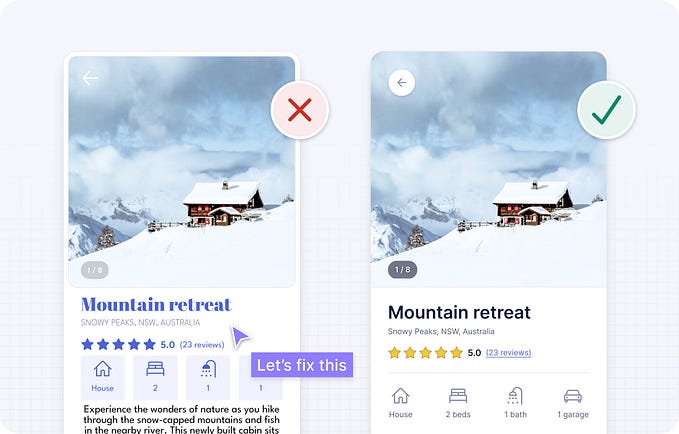

We have commonly used social acceptance in product design, through thumbs-up, likes, hearts, and other reward mechanisms. Now let’s see how social exclusion could be used to persuade the user in the below examples of a social network and LinkedIn:

In these instances, the usage of loss aversion along with social exclusion makes it more effective. This encourages users to think that leaving a website is equitable to leaving their favorite people and communities behind i.e, getting socially excluded.

Tristan Harris gave a wonderful ethical example of social inclusion persuasion in his article.

Conclusion

The usage of social heuristics such as social proof, social comparison, social rejection, and social inclusion in product design can be used to increase user engagement and reduce churn. Many companies use psychological manipulation to entice users and influence their decision to maximize profit. As technology is increasingly shaping our social fabric, there is a great responsibility for creators to use it in an ethical manner.

Thanks for reading! If you found this article helpful, send some 👏👏👏 to help others find it too! This will tell me to write more of it!