Why You Might Be Set Up for Failure in Your UX Position

So, you’ve just landed a new UX design job, but something is amiss. Whether this is your first gig, or many gigs into your career, you may find yourself in a particular situation that often times will prove to be incompatible with the very job responsibilities you were hired to fulfill.

UX As A Discipline

Before detailing that situation, it’s important to call a few things to mind about the nature of user experience design. Broadly speaking, UX design, or UXD, is most effective when treated as a discipline — as opposed to a single role or career path. It spans the entire product design and development process, from ideation to release, and eventually maintenance. In the ideal scenario, the user’s needs are considered at every stage of a product’s lifecycle.

Because of this broad application across processes that aim to transform an abstract idea into a “concrete,” releasable product, UXD activities can similarly be categorized into the strategic (abstract in scope) and the tactical (concrete in scope). Both kinds of activities are necessary for a successful user experience.

The Problem: Stuck in Tactical UX

With that in mind, we can delve into the details of your current situation, and begin to understand why it might be a big problem. The situation is this: your position is in the technology organization of a company, as opposed to the product, business or marketing organization. In other words, you answer to the same middle or upper management as the development teams, meaning that your organization is mainly focused on tactical, technology-related concerns (or else believes it is best-positioned to make choices on behalf of the user). While good UXD takes the technology aspect into account, it shouldn’t be the primary or only consideration.

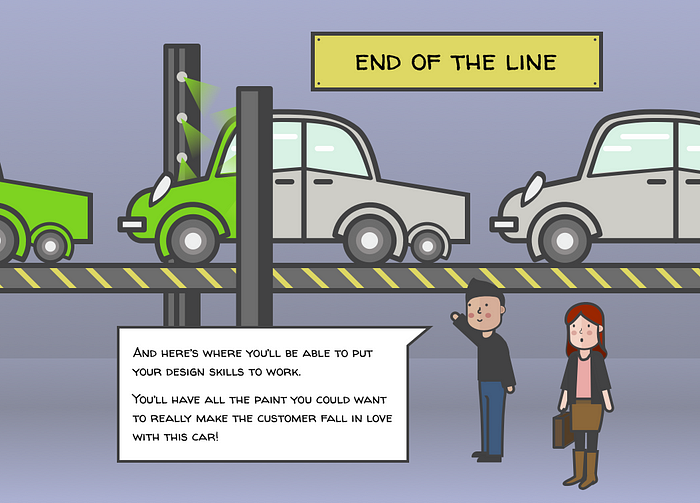

When you are part of a technology organization, any change you will be able to affect on a product will be in the capacity of a UI designer, on a tactical-level, at the end of the production line, so to speak. You will likely not have been present in earlier discussions wherein a user was analyzed, and her needs teased out of the data — or know whether these conversations even took place at all. You won’t understand the reasoning behind the business decisions, nor will you have insight into any underlying use-cases. You will be given requirements you don’t understand, often with wireframes and interaction instructions already provided, and yet be tasked with delighting the end-user.

While it’s true that the user interface is fundamental to a digital experience, it is itself a product of the process, and its ability to delight users is only as effective as the deliberate thought and planning that went into it. By the time you have the opportunity to contribute, many hands will have — knowingly, or more likely unknowingly — already fashioned the user experience.

In this limited, tactical function of UI designer, as you deliver on interaction and visual design, you’ll be doing so on a reactive basis, according to the needs of the developers, who in turn are responding to requests made of them. Under more ideal circumstances, this would be a perfectly natural and expected step of the experience design process — but this part should never be a substitute for the whole.

A reasonable person may be wondering at this point why a company would be so short-sighted when it comes to the lack of a deliberate user experience design process, which would seem to indicate a general indifference to their own customers’ satisfaction. There are a myriad of reasons, but most often, said companies don’t have a mature product design process, and so aren’t doing the due diligence of properly researching their customers and addressing the right needs. In that context, hiring a UX designer into the technology organization makes as much sense as anything else. User experience design is an extension of core product design activities, and so is dependent upon them being at least somewhat in place (another topic for another time).

By extension, many technology-centered companies are convinced that the development organization is equipped enough to anticipate and address these customer needs, an assumption that all too often results in consumer products that are designed by programmers, and which either miss the mark with the user base, or prioritize compatibility with the current technology platform over the end-user’s experience…or both.

What Now?

If you do happen to find yourself in this situation, it is neither the end of the world for you, nor for your career. I have worked in this capacity, and I have known others who were content enough to be in a similar situation. What it DOES mean is that if you are being held accountable by your employer for the full user experience, good or bad, and you are not enabled to deliver on those expectations, you are being set up for failure. Assuming you aren’t content with the circumstances, what is a UX professional to do, aside from updating her resume?

If you work for a small- to medium-sized company, your options are:

A. Hunker down and just do the work. It’s a paycheck, after all.

B. Retroactively create the strategic user-experience deliverables, such as personas, use-cases, user flows, sitemaps, etc. — if only for your own benefit — while taking on the role of a UX evangelist.

If you work for a larger company, where Option B might be fairly problematic, you have these additional options:

C. Determine whether your company is large and segmented enough that you can treat your particular branch or sector as its own small business entity; if so, proceed with Option B.

D. Seek out a centralized product, business or marketing unit, and bide your time until they have a UX designer opening.

Option B: Create UX Strategy

For the sake of productive discussion, let’s assume you choose Option B. Here’s how you would proceed:

1. Talk to others internally (leadership, management, developers, everyone), to learn as much as you can about the product’s end-user. If there isn’t a clear idea about who that end-user is, expect (and accept) other unusual, but equally valid answers, such as shareholders and internal stakeholders. These are all users, after all, and technically, you are solving a problem for them (another good topic for another time). Plus, you have the added benefit of having created some concrete evidence as to why you can’t please the actual end-user of the system, if you are to be held accountable. If you are displeased with the result of this research, and have an extra amount of determination and ambition, then…

2. Insert yourself into as many brain-storming discussions as possible with the decision-makers. Crash meetings. Ask questions about the product. Make suggestions, and make documents that no one has really asked for, including primers on user experience. And for the sake of your success in all of this effort, find an internal advocate! This last point is key; if you can’t get anyone with influence on your side, change toward user-centered design is very unlikely, and though your battle may be a good one, it is likely futile.

If you keep asking enough “why” questions to the right people to formulate your UX self-deliverables, others are going to take interest in that documentation, see the value in what you’re doing — at which point they might just become real deliverables — and you can start to see UX practices permeate existing thought processes.

Conclusion

Best-case scenario: As UX design practices become implanted into your company’s culture, they could actually help to grow the company’s strategic capacity. You might end up turning decision makers into user-centered design thinkers. Eventually, management may make provisions for a product or UX design department that doesn’t answer to another internal organization, or at the very least redefine your responsibilities to include participation in the ideation and research phases. And if none of this pans out…hopefully you’ve learned something new, gained some new perspective, and can enrich your resume.